Bank Robbery - Richfield State Bank

On the morning of July 11, 1932, two men in blue shirts and overalls sidled up to the teller's cage of Richard Hackbarth, the lone occupant of the Richfield State Bank of Richfield, Wisconsin.

"What can I do for you, gentlemen?" Hackbarth asked. "Plenty!" snapped one of the men and whipped a revolver from his pocket. "This is a stick-up. One false move and I'll drill you." Hackbarth hesitated. His hands went up slowly, but his foot edged toward the alarm button on the floor. The description of the two made him suspect that the gunmen might be the ones who held up the Eldorado, Wisconsin bank four months earlier. He knew he was gambling with his life, but he felt it was worth it.  His foot touched off the alarm. Instantly a strident gong reverberated through the lobby and bells clanged in several boxes outside the bank.

His foot touched off the alarm. Instantly a strident gong reverberated through the lobby and bells clanged in several boxes outside the bank.

The armed gunman spun at the sound of the alarm, then swung back at the brave cashier. "Smart guy, eh?" he sneered coolly. "Well, take this." His pistol roared. A bullet smashed through the chest of the cashier. Hackbarth slumped to the floor, badly wounded. "Come on, grab what cash there is and let's get out of here!" the gunman ordered his accomplice. They ran behind the cages, gathered $700 in cash lying on the counters, jammed the loot into their pockets, and dashed to their car where a third man was waiting.

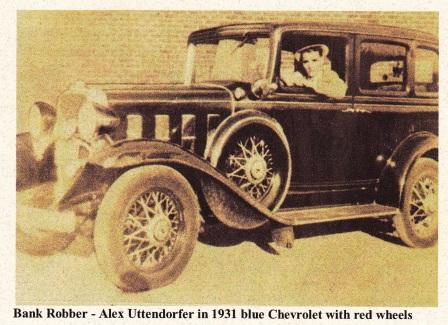

Townspeople, startled by the alarm, ran to the street in time to see the getaway car, a 1931 blue Chevrolet with red wheels and Minnesota plates, speed from town. A posse was quickly organized by Deputy Sheriff Peter Schwamb who lived above the bank. Over the smooth county highways raced the pursuers, guns ready, eyes alert, seeking the ruthless gunmen who had shot one of their most respected citizens.

Townspeople, startled by the alarm, ran to the street in time to see the getaway car, a 1931 blue Chevrolet with red wheels and Minnesota plates, speed from town. A posse was quickly organized by Deputy Sheriff Peter Schwamb who lived above the bank. Over the smooth county highways raced the pursuers, guns ready, eyes alert, seeking the ruthless gunmen who had shot one of their most respected citizens.

Back at Richfield, a call went out to block all roads. An airplane took off to aid in the chase. The wounded cashier was packed into an ambulance and rushed to the nearest hospital at Hartford.

Sheriff Holtebeck interviewed townsmen who had seen the flight of the gunmen. From the descriptions he was convinced that two of the men were those who had robbed the Eldorado bank. This time, however, they had a third man for a lookout and chauffeur. And, this time they had shot a man in cold blood. They were growing professional and dangerous.

Holtebeck was chagrined to find that so quickly did the bandits rob and flee that no one had been able to remember the license number on the automobile. The frantic pursuit seemed useless. Hours passed, hours during which the robbers had ample time to reach safety.

Holtebeck was chagrined to find that so quickly did the bandits rob and flee that no one had been able to remember the license number on the automobile. The frantic pursuit seemed useless. Hours passed, hours during which the robbers had ample time to reach safety.

Long hours later a motorist on a county highway near Vernon in Waukesha County braked his car to a skidding stop. He leaped out and ran back to the 1931 Chevrolet lying on its side in the ditch, two wheels still spinning. Two men, dazed and cut, were crawling through the windows of the wrecked car.

"Are you hurt badly?" the motorist asked anxiously. "Here, I'll drive you to the hospital." One of the men wiped the blood from his forehead. "We're all right, buddy,'' he said, "beat it." "But you're hurt. You need help." "Beat it, I said," repeated the man clad in a blue shirt and overalls. Then he checked himself. "Wait a minute. Help us get our car out of the ditch." "Sure." The motorist ran over to the other side of the car and assisted the men in righting the overturned car. As the car was being lifted, a bundle of bills tumbled to the ground. One of the men reached down and stuffed the bills in his pocket. "Well, what are you staring at?" he demanded, glaring at the motorist. "Nothing." "Okay, then beat it."

The man returned to his car, puzzled. Why did these men, shaken up and hurt, refuse help? And, what was the significance of the large bundle of bills that fell from the car? The motorist had heard nothing of a bank robbery. But, obviously something was very wrong here. He took down the Minnesota license number and reported it to the sheriff. He was amazed to learn that his chance discovery of an accident had provided a clue to the trail that scores of officers were seeking.

Little wonder the Minnesota police had a difficult time tracing the owner of the license plate on the accident car. The car had been sold and resold and finally wound up in the name of Alex Uttendorfer of Lake Elmo, Minnesota. Lake Elmo police reported Uttendorfer had left six weeks before for Minneapolis. His description tallied with that of the gunman with the itching trigger finger who had held up the Richfield bank, but beyond that Minnesota police knew nothing about him. He had no record and had never been in trouble.

After much searching, it was discovered that Uttendorfer originally lived in the Fond du Lac area. The Sheriff found his home and talked with his father, a quiet, respected farmer. Alex had not been home for a month. He liked to roam around. He had two brothers, Joe and Louis. The brothers weren’t home either. No one had any idea where Alex was but someone said that he had met a girl and was madly in love with her.

"Find the girl, and we'll find the Uttendorfer brothers," the sheriff told a corp of detectives and deputies. "All we have to work on is a description of the brothers and a Minnesota license plate. We don't even have the name or description of the girl, but we'll have to make the most of what clues we have."

Two days had elapsed since the Richfield holdup, precious time during which the bandits could have put hundreds of miles between them and local authorities. Hackbarth was holding his own at the hospital, but he was far from being out of danger. Any hour might see the charges changed to murder.

A squad of detectives began a systematic canvass of taverns and night spots. If the brothers had lingered in the city for a "farewell" party, the trail might still be warm. The hunt was under way. Late that night the telephone jangled at the Fond du Lac police headquarters. "I want to report a reckless hit-and-run driver," an irate voice shouted. "A couple of fellows driving a car with a Minnesota tag smashed into my car a couple of minutes ago, and when I got out to talk to them, they shoved the car into gear and sped away. I demand you do something about it!" A moment later a general alarm was broadcast to all cruising squad cars and motorcycle officers. Peering into the darkness, nerves tense, officers intensified the manhunt throughout the county.

Half an hour later Officers James Silgen, Jr. and Robert Thinney, cruising in their squad car, spotted an automobile with Minnesota plates parked deep in the shadows of a side street. They could make out the shadowy forms of two men in the car. "Let's wait before arresting them," Officer Thinney suggested. After a few minutes the car pulled away from the curb and headed uptown toward the rooming and apartment house district. It stopped before an apartment house and two short blasts from the automobile horn split the silence. A moment later the front door opened and a young woman stepped to the curb. She was carrying two suitcases, one in each hand. A hand reached from the interior of the car to assist her, and she quickly climbed inside.

The squad car leaped from the curb, cut in sharply in front of the slowly moving automobile. Silgen and Thinney piled out, their guns ready for action. "All right, get out and don't make a false move," Silgen directed. The right rear door flew open. A dark figure sprang from the car and began running down the street. Silgen took after him. With five long strides he was on him, swung him around sharply by the shoulders.

Officer Thinney was having his hands full. The driver of the car suddenly jammed the auto into reverse, and only after leaping on the running board and twisting the wheel from the driver's hands, was Thinney able to subdue him.

The two suspects and the girl were taken to headquarters where the men were speedily identified as Louis and Joe Uttendorfer. When they vehemently denied any knowledge of the bank robberies, all three were taken to separate cells. Immediately the sheriff sensed little would be gotten from Joe. Louis, on the other hand, was more volatile and highly nervous. The youth said he and his brother had been looking for work in Fond du Lac, Oshkosh and Milwaukee but could not name places where they had applied for jobs. He staunchly proclaimed his innocence, asserting that he had not seen his brother, Alex, in more than a month.

The two suspects and the girl were taken to headquarters where the men were speedily identified as Louis and Joe Uttendorfer. When they vehemently denied any knowledge of the bank robberies, all three were taken to separate cells. Immediately the sheriff sensed little would be gotten from Joe. Louis, on the other hand, was more volatile and highly nervous. The youth said he and his brother had been looking for work in Fond du Lac, Oshkosh and Milwaukee but could not name places where they had applied for jobs. He staunchly proclaimed his innocence, asserting that he had not seen his brother, Alex, in more than a month.

"Where's Alex now?" demanded the sheriff. Louis shifted uneasily in his chair. "You've got me," he said. "Alex never tells anyone where he goes." "He just left us his car and blew town."

Next Holtebeck questioned the girl, a comely young woman with auburn hair that swept down in waves around her shoulders, a healthy complexion, and wide frightened eyes. She seemed hardly the type for a gunman's moll, the sheriff thought.

She was obviously scared. What little she knew she told the sheriff is a gush of words: "I was in love with Joe. He used to come and see me quite often and bring me expensive gifts and show me a good time. Two nights ago he came to town again. He seemed highly nervous. Finally I asked him what was wrong. "I'm hot. The cops are after us for a job Alex, Louis and I pulled," he said. "We've got to beat it to Canada. Will you come with me? l was so scared I couldn't think. At the moment, I only knew that I loved Joe and would go to the end of the earth with him. So they took me home to pack my clothes and went to hide out until I was ready. The rest you know." "Was Alex supposed to go with you?" Holteback asked. "No, Alex left yesterday for Milwaukee where he has a girl. The boys wouldn't tell me her name."

Pausing only to notify the Milwaukee police to watch for Alex Uttendorfer, Holtebeck bundled the brothers into a car and rushed them to Hartford, where Cashier Hackbarth had passed the crisis and was now definitely on the way to recovery. At the hospital, Hackbarth raised himself weakly on his elbows and looked searchingly at the brothers. "That's one of the men!" he cried pointing to Joe. "I'll never forget that face as long as I live!"

The brothers were brought into court shortly thereafter and pleaded guilty to the Richfield holdup. Each was sentenced to 15 to 40 years in the state prison. The mystery was solved and the bandit trio was broken.

But the hunt had just begun for the ringleader of the gang, a hardened criminal now known to have served his apprenticeship in big time crime circles. The sheriff called on the Milwaukee police. Within a few hours the officers had found the family of the girl, Isabelle Pliska better known as "Mickey." And, the trail led immediately to a cottage on Wind Lake where Alex was reported to have been hiding. The officers formed a posse and sped to the cabin rented by the bandit leader. Here the officers learned the mettle of their quarry. Uttendorfer had been watching for them. In a flash the bandit and his 18-year-old girl friend leaped through a rear window into the underbrush. A hail of bullets followed them but only echoes responded to the firing. Alex and the girl took a devious but carefully prepared trail to a car hidden on a side road.

For the third time Alex outdistanced the pursuit and for the third time with amazing ease he vanished almost in the midst of the heavy ring of officers. Uttendorfer and Mickey subsequently mocked the officers by popping up the following day at a roadhouse in central Wisconsin where Alex coolly robbed the owner of several hundred dollars. The pair appeared next in Milwaukee, then in Minneapolis. The brief series of robberies ended suddenly, and the trail of the Romeo bandit and his girl disappeared completely. Week after week, month after month, the police pressed their search running down countless clues, following scores of false leads.

In December, 1932 a series of robberies and holdups broke out in northwestern Wisconsin and eastern Minnesota. Always the bandit was a slim youth with curly black hair and an ugly disposition. Everything from five cents to $5,000 was legitimate loot with him.  Sometimes he worked alone, and sometimes a young woman sat outside waiting at the wheel of the car. Description of the pair soon led to their Identification as Alex Uttendorfer and "Mickey"Pliska.

Sometimes he worked alone, and sometimes a young woman sat outside waiting at the wheel of the car. Description of the pair soon led to their Identification as Alex Uttendorfer and "Mickey"Pliska.

By carefully plotting every scrap of information, the authorities theorized the gunman's base was somewhere near Lake Johanna, Minnesota. Several days of sleuthing in nearby communities revealed that a young man and girl answering the descriptions of the outlaws were living in a cottage deep in the woods near Lake Johanna. Just before dawn on December 28, a score of detectives and deputies hid in the woods surrounding the cabin and waited for daylight before closing in. Dawn came and the men drew their guns ready to advance. Suddenly the door of the cabin opened and a young man stepped into view. It was Alex Uttendorfer. A nickel-plated revolver gleamed menacingly in his hand as he glanced furtively about.

A shot rang out. The bullet grazed the youth's head. Instantly he fired once in the direction of the deputies, then dashed back into the house. The men had to strike fast now. They advanced cautiously toward the cottage, their guns ready for action.

"Come out, Uttendorfer, or we'll blast you out!" In tense silence, the cabin door opened and Uttendorfer ran out, a blazing pistol in each hand. Behind him ran the slim form of a young woman, lugging a small grip under her arm. The officers opened a heavy fire, but the fugitive pair miraculously tore through a curtain of bullets. They dashed for their auto parked on a side road about 50 feet from the cottage.

The charmed luck of the outlaw pair was at their side again that day. They managed to reach their car with only a flesh wound apiece, and the outlaw pair sped away in a torrent of lead. The Romeo bank bandit knew the wilds of Minnesota as well as any man in the posse. Within an hour he managed to lose the officers and disappeared somewhere in a heavily wooded section of northwestern Wisconsin. But he was hot, too, in that area. They were spotted in Nebraska the following day, headed west, but again eluded a hastily formed posse. As usual, no trace of them could be found.

Then, on the morning of December 31, three days after the Minnesota gun battle, a travel weary youth and his exhausted girl companion pulled into a garage on the outskirts of Mt. Vernon, Washington. Their car covered in grim and dust was badly in need of repairs. "Fix 'er up," the youth told the attendant. "We'll be back late this afternoon to pick it up."After the pair had left, the attendant began a routine examination of the car which bore Minnesota license tags. Suddenly he straightened up, startled. The rear of the car was spotted with bullet holes. He hurried to telephone the police.

Late that afternoon the youth and his girl returned to the garage. "All set?" he asked the attendant. "Yes, sir. It's in tip top shape.'' He led the pair to the dimmed rear of the garage where the car was parked. Out of the darkness, a voice suddenly boomed: "Don't move, Uttendorfer! We've got you covered!" Alex Uttendorfer reached fast for his gun, then stopped quickly as the muzzles of five guns jabbed into his ribs. "Okay, you've got me," he said sullenly.

A week later Alex Uttendorfer and Isabell Pliska were returned to Wisconsin. Despite accusations by his brothers and witnesses, Alex steadfastly maintained his innocence and elected to stand trial. He was charged with robbing the Richfield State Bank and went on trial February 9, 1933. As the overwhelming evidence began to pile up against him, he suddenly decided to throw himself on the mercy of the court and changed his plea to guilty. He was sentenced to 15 to 40 years for his part in the Richfield holdup and 3 to 30 years for shooting Cashier Hackbarth, who had recovered.

"Mickey" Pliska, the 18-year-old girl, who longed for adventure and the thrill of living with an outlaw gunman, was sentenced to a house of correction until she was 21.

(Excerpted from "Startling Detective" April, 1940. Magazine article by George S. Hymer and provided by Oscar Hackbarth, son of the Richfield State bank cashier.)

Enjoy our other stories