Great-Grandmother Salome

Written by Lillian Motz

Bauer

My Great-Grandmother, Salome Mallow Motz, must have been quite a woman. I should not really call her my grandmother, for she was the grandmother of a good percentage of the population of the extreme southeastern corner of Washington County before the age of subdivisions.

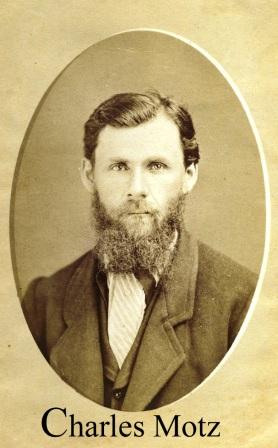

Great-Grandmother, Salome, was born in Hessen, Darmstadt, Germany in  1806. In 1838, she and her husband, Godfried Motz, and three very small children came to New York by sailboat. My Grandfather, Charles Motz, was born in the state of New York. In 1843, the family came to Milwaukee via the Erie Barge Canal and the Great Lakes.

1806. In 1838, she and her husband, Godfried Motz, and three very small children came to New York by sailboat. My Grandfather, Charles Motz, was born in the state of New York. In 1843, the family came to Milwaukee via the Erie Barge Canal and the Great Lakes.

They purchased land located in the Town of Richfield (Village of Richfield), where there was a small Hessen, Darmstadt settlement.

It is hard to visualize how they survived those first few years, virtually living off the land on wild game and fish. In the summer edible roots were collected and dried. Blackberries, red and black raspberries, elderberries, gooseberries and strawberries were gathered and preserved. Honey was taken from trees where wild bee swarms had stored it. Maple sap was gathered and cooked down into syrup and sugar. All kinds of nuts were gathered and stored. Camomile and other leaves were gathered for tea.

It is hard to visualize how they survived those first few years, virtually living off the land on wild game and fish. In the summer edible roots were collected and dried. Blackberries, red and black raspberries, elderberries, gooseberries and strawberries were gathered and preserved. Honey was taken from trees where wild bee swarms had stored it. Maple sap was gathered and cooked down into syrup and sugar. All kinds of nuts were gathered and stored. Camomile and other leaves were gathered for tea.

In those days, it was important to keep live coals of fire at all times for starting the next cooking of meals. If the fire accidentally went out, you were embarrassed and had to borrow hot coals from a neighbor and, undoubtedly, were considered a poor housekeeper. There were no matches, and if there were, who had money to buy them?

Salome's house was built of logs near a pond, which was produced by a spring. The water for the house had to be carried, and she did her washing at the pond. The animals, which were acquired later, also went to the pond to drink. Salome made her own soap. First the wood ashes had to be saved and properly handled by adding water which eventually produced lye. Then, by cooking the correct amount of animal fat, lye and salt, soap was made.

The first real crop of grain was a thankful Godsend. Wheat and barley were roasted for coffee. Wheat was taken to a mill and stone ground. The outer layers were used for animal feed, and the cleaner finer meal used to make porridge, which was the staple breakfast menu. The flour made very good bread and biscuits. Cake was unheard of. The nearest one got to it was to make the dough a little richer and sweeter and sprinkle maple sugar or honey on top. Yeast was another baking problem. You had to have a "starter," usually borrowed from someone. The day before baking you added the water in which the potatoes were cooked to the "starter," also some sugar. You let it stand in a warm place over night and hoped it would "work." The next morning, if it was nice and foamy, you used it as a rising agent for the bread. You always saved one and one-half to two cups in a covered container for the next baking.

Vegetable gardens were very important in those days. "What you didn't raise, you didn't eat." Your first seeds were always borrowed from a neighbor or relative, and after that you gathered, dried and stored your own seeds.

Salome never heard of "Women's Lib," but when her husband, Godfried, went to a meeting, especially a church meeting; he was well briefed before he left home. It was through her prodding that Zion Evangelical  Church of Colgate was organized in 1846.

Church of Colgate was organized in 1846.

Salome raised six children, and when her oldest daughter died leaving a small son, she took him home and raised him as her own. Three of her sons served in the Civil War. All returned home, however one had been a prisoner of war and confined at Libby Prison and another spent months at a hospital for veterans at Keokuk, Iowa.

After her family was grown and her husband died, she lived alone for 20 years. She kept her cow and chickens and made a small garden. Her needs were small. She was a happy, singing, Christian woman - always doing good for others and entertaining them with her humor. She sang all the way to church, all the way home and everywhere she walked. Everyone walked in those days.

Once a year the church had a Camp Meeting in Menomonee Falls for several days. Salome wouldn't miss that. She led her cow along and tied it to a tree on the edge of the grounds. She hid an extra pan of grain behind the door of the chicken coop, hoping the chickens wouldn't find it for a day or two.

She walked to Milwaukee every few weeks to deliver butter and eggs to her friends. She left home right after midnight so she would arrive there before the sun was hot and the butter would melt.

My Father Walter Motz, must have been a lot like her. He had a wonderful  sense of humor until the day he died at the age of 98 years. He often embarrassed his hostess by commenting that "Jello was the next thing to nothing anyone could eat."

sense of humor until the day he died at the age of 98 years. He often embarrassed his hostess by commenting that "Jello was the next thing to nothing anyone could eat."

I am proud of my heritage and owe much to these simple and courageous people who are my forebearers, especially Great-Grandmother Salome.

Hope you enjoyed this story

Enjoy our other stories