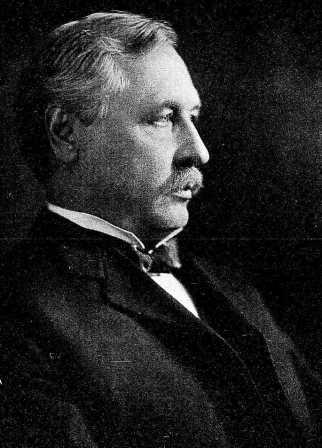

Albert Earling - Richfield Native Becomes Railroad President

Albert J. Earling, Born in Richfield, Wisconsin

President of the Milwaukee Road Railroad

The turn of the century was a time of great change for the Milwaukee Road From the directors of the road to the lines themselves, change was the order of the day.

In 1899, President Roswell Miller relinquished the presidency to Albert J. Earling and moved on to the chairmanship of the board of directors. Earling, another Wisconsin-born railroader, entered the service of the Milwaukee at age 17.

Born at Richfield, Wisconsin in 1849, he had been with the Milwaukee since 1866 having began as a telegrapher at Rugby Junction, Richfield Township, Wisconsin.

He had been promoted to train dispatcher; then he became an assistant superintendent for four years, and for two more years thereafter he was a division superintendent. From assistant superintendent, he became general superintendent of the Milwaukee lines in 1888; and, two years later was made general manager, an office he held for five years. In 1895, he was made second vice president.

Earling was another of the young men who had come into the railroad in the heyday of Mitchell' s leadership. He was to become inventor of the block signal system, and he was destined to be one of the most popular of executives. Having risen from the ranks, he kept in touch unfailingly with the men of the Milwaukee, spending many nights in the yard riding switch engines and talking with the men.

The Seventh Son

By Harriet Earling Dake-Milwaukee (Excerpted from thefirst chapter in the biography of Albert J.Earling, third president of the Milwaukee Road, written by his daughter, Harriet Earling Dake.)

Many times I have heard my father tell of the first time he saw a railroad train. He was among the boys, in the summer of 1863, who sat perched on the rail fence along the newly laid tracks of the Milwaukee and St. Paul  Railway. They were waiting for the iron horse which was to make its first trip from Milwaukee to Rugby Junction. Eagerly he kept his intense blue eyes toward the east, following the shining tracks as far as he could see.

Railway. They were waiting for the iron horse which was to make its first trip from Milwaukee to Rugby Junction. Eagerly he kept his intense blue eyes toward the east, following the shining tracks as far as he could see.

Occasionally he turned to look at the crowds gathering round the tiny new station house, for the mayor had declared a holiday for the occasion and all the stores and schools were closed. As a loud whistle sounded in the distance, farmers grabbed their horses, mothers clutched their children and he gripped the rail. The roaring, burning monster bore down toward them, and in fear the boys fell backward off the fence - all except one Adelbert Oehrling, his heart beating with the rhythm of the puffing snorting engine as it slowed down for the stop. Then he followed the curious people through the cars, marveling at the seats, the real glass in the windows and the hanging kerosene lamps. As he left, a man tapped him on the shoulder. "Sonny," he said, "You better plan to be a railroad man when you grow up. It's a thrilling life."

At the station house, he peeked through the window to look once more at the clicking keys of the telegraph instruments and wondered again how messages could be transmitted to the paper the station master was handing to the conductor. This young man, only slightly older than Adelbert, was station master, train dispatcher and telegraph operator all in one. He made up his mind to ask him.

As Adelbert headed toward his home in Richfield, two miles up the track, he seemed to be in step with that insistent clickity-click and throbbing in his head were the words - plan to be a railroad man. Plan to be a railroad man, he thought bitterly, as his pulse slowed down to the weary trudge of his feet. He was sixteen now, and his father had apprenticed him to a cobbler. Whatever decisions Constant Oehrling reached for his ten sons were irrevocable and final.

It was this decision that Adelbert was to become a shoemaker that worried him on that two mile walk back to Richfield from Rugby after his first sight of a railroad train. He had heard much about the supposed luck of the seventh son, but there was no luck in trying to make a cobbler of a boy who had made up his mind to become a railroad man.

At home that night, Adelbert went about his chores so quietly that his mother asked if seeing the train wasn't as exciting as he had expected it to be. "Yes, it was even more wonderful," he replied. So wonderful, that he wanted to become a telegraph operator and work for the railroad. In that case, his father roared, he might as well get the pick and shovel from the shed and start working with the road gang. But as long as he remained at home, he would be expected to obey his father and the cobbler to whom he was in honor bound to serve.

His mother, Elizabeth, agreed that he must continue his shoe making lessons but suggested that he ask the telegraph operator to teach him telegraphy in the evenings. In exchange for this, she would send a lunch for him as he was on duty until after midnight; and she knew the family with whom be boarded did not provide a midnight lunch. The man was pleased with the plan for he had heard of Mrs. Oehrling's fine French cooking. Also it meant a break in the solitude of that dismal place where night after night no message came, and moreover he liked the boy with his keen intelligent and determined ambition.

Besides school work and chores on the farm, it would make a long day for Adelbert, but he was anxious to try to do it. Elizabeth said she would see to it that he could slip out of the store at nine o'clock, a half hour before closing time; but he must return by ten-thirty-unbeknown to any members of the family. He promised not to mention it to his brothers or his friends, and they both refrained from saying they would not tell Constant, but both understood. Elizabeth must have felt there was something very special about this seventh son to take such a chance of incurring her husband's wrath.

Every evening Adelbert walked the two miles to the little station at Rugby  Junction to study the mystery dots and dashes, carrying a bag of flaky biscuits with current conserves, French bread with chicken livers, home-made sausage on fresh rye bread or an apple tart, and always a jar of fresh coffee.

Junction to study the mystery dots and dashes, carrying a bag of flaky biscuits with current conserves, French bread with chicken livers, home-made sausage on fresh rye bread or an apple tart, and always a jar of fresh coffee.

With regular evening work and sometimes helping around the station on Sundays, Adelbert was soon sending practice messages on a dead wire, but he could not receive any because his initials A. 0. were not good telegraph material. The operator explained that most operators were contacted by calling their initials, and three letters were better than two. On the way home Adelbert wondered how he could get a middle name, but, as usual, his mother had the solution. He was to be confirmed within a month. John was a good English name, and they would ask the pastor to use it. In the meantime she would prepare Constant for this addition, and also she suggested the change in spelling and pronunciation of his first name from Adelbert to Albert. It would be more in keeping with American ways and living.

One night in April, 1865, Albert came home so excited that he could hardly steady his voice to tell his mother that now he was an operator sending and receiving messages with his own call letters, A.J.0., but over dead wires, he explained. But the operator said he would be ready to accept a position as operator at the close of the school year and would recommend him to the superintendent. Elizabeth was radiant, but she realized that it was going to be difficult to tell Constant how she had helped Albert acquire this knowledge. She felt it would be better to wait until June before breaking the news to him, as school would be over. Albert was in the highest grade and was seventeen. Also, he would have finished his apprenticeship.

In preparation for this, Albert had taught his younger brother how to keep the accounts at the store and to help with the buying. His eldest brother, Peter, was still at University at Heidelberg. Jacob and Friedrich had finished school and Jacob was in charge of the farm. Friedrich had learned the building of telegraph lines, but was still living at home. So there was no reason not to accept the offer when it came.

The offer came in June for the position of night operator at Whitewater. Albert broke the news to his mother; but while she rejoiced with him, tears came to her eyes as she realized he must leave home. Of course, the task of telling his father worried Albert, sine he knew nothing of the secret lessons. Elizabeth offered to tell him and take the consequences, but Albert insisted he must now take his own stand and did not want his mother to shield him any longer. Therefore, he went to his father now confined to his chair most of the time, and showed him the letter offering him the position. He explained how he had trained under the operator at Rugby Junction, but did not mention the payment in midnight lunches for the instruction received. Constant stormed in wrath in loud guttural German, the louder because he was not able to stand on his feet.

You are an ingrate! I gave you the chance to become a cobbler, and then you could pay me back by taking care of the store. Just then there came a timely knock at the door as the Rugby operator and an official of the telegraph company came with the contract for Albert to sign. Constant seemed to be somewhat impressed by the important looking document, but growled, "I will have no part of this. If Albert makes a failure of it, he needn't return to my roof for protection and help."

When the time came for Albert to leave, Elizabeth had softened Constant's anger to the extent that he would give the boy two shirts and a suit of clothes - his first. His mother gave him a pocketbook of money she had saved from gifts from her father. "Albert," she said, "this money is for you to buy shoes, and an overcoat and a hat. There will be a little left for you to pay for your board and room until you get your first salary. I have knitted woolen socks and gloves for you. It is a source of great pride to me that you have prepared yourself and obtained such a fine job."

"Mother, I owe it all to you." His voice was unsteady. "Whatever I accomplish, you have made possible. But I will make good. I want you to be proud of me."

Whitewater was 75 miles from Richfield by team, but by train one had to go to Milwaukee and change trains. It was practically an all day trip, but not too long in Albert's anticipation of his first ride on the railroad. All of his brothers and cousins who were at home and his friends and neighbors for miles around gathered about the little station at Rugby Junction, as they had a little more than a year before when the first train came  through. With equal tension they watched now as the country-bred boy in his home-made clothes, boarded the train for the first time - the train that eventually carried him to the presidency of The Milwaukee Road.

through. With equal tension they watched now as the country-bred boy in his home-made clothes, boarded the train for the first time - the train that eventually carried him to the presidency of The Milwaukee Road.

Elizabeth dressed in her best alpaca handed him a package as he climbed aboard. "This is the lunch for the new telegraph operator at Whitewater." "All aboard!" shouted the conductor. From the platform of the train Albert waved to the crowd and sent a special grateful glance to the operator in the station door - the man who started him in the railroad service and whose name, unfortunately, has not been preserved for posterity.

Hope you enjoyed this story

Enjoy our other Stories